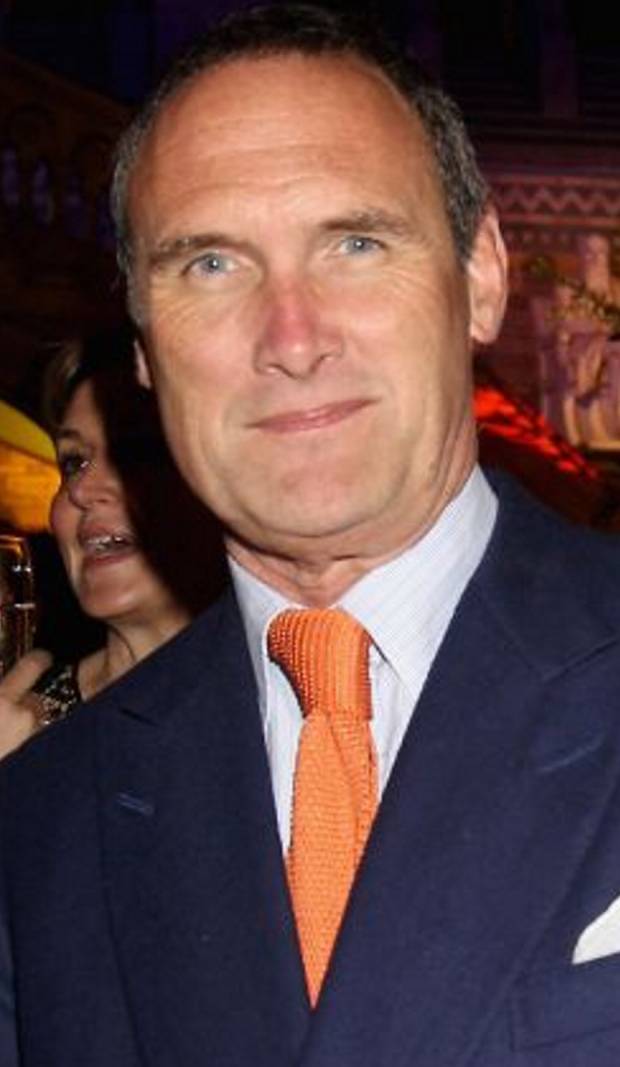

A.A. Gill

(1954-2016)

Posted: 15 December 2016

I met Adrian Gill for the first time in the spring of 1992, nearly a quarter of a century ago. In those days I still saw a bit of the potter Emma Bridgewater and her husband Matthew Rice, best known now for his exquisite illustrated books on architectural history. I still keep some pens in a lovely little box he made, each side is a different composition united under a hefty, Wren-ian cornice.

Emma and Matthew thought that Adrian might be of some use in promoting my book on Brillat-Savarin, which came out that June. I am not sure they told me who he was or how he was going to do it, but I was happy to come to dinner anyway. Matthew was a superb cook and dinner was always fascinating as he often served up something he’d shot at home in Norfolk. So I met Adrian and his then wife Amber. I also met a little Gill, a mere babe in arms. Amber naturally seemed most preoccupied with that. They struck me as decent sorts, and Adrian duly evinced a desire to write up the book and I had a copy sent off to him the next day. Later I saw he had written nice things about it in the Tatler where he had been invited to pen a column on food some months before. Amber Gill (as everybody will know by now) is better known as Amber Rudd these days, and she is our Home Secretary.

After Adrian died last week I saw that Amber had been his second wife. He had been married first to Cressida Connolly, daughter of the famous man-of-letters Cyril. I had known Cressida when she was a schoolgirl in Oxford although we fell out, quite seriously, and I have not seen her since. Her mother remarried the former Jesuit, poet and classicist Peter Levi, who wrote what was possibly the most fulsome review I have ever received for a book – come to think of it, it was for Brillat-Savarin. It occurs to me that Cressida may have introduced Adrian to Emma – as they were schoolgirls in Oxford at the same time, but I suppose he might also have been at art school with Matthew. He still described himself to me as a painter when we met that spring and he had yet to make the final leap into journalism.

I can’t recall whether Adrian came to the launch of the book at 50, Albemarle Street. It was a good party: Gosset champagne from Fields, a vast, decorated festive loaf made by Jackie Lesellier together with Brillat-Savarin and other cheeses from my friend Michael Day and his Huge Cheese Company. We even induced Campbell Distillers to supply a case of Wild Turkey bourbon to make mint juleps, but I don’t think anyone drank any. The bottles seemed to have disappeared into a voluminous cupboard by the end of the bash.

The following year Adrian was translated to the Sunday Times and very soon he was one of the most famous journalists in Britain, to the degree that his outrageous remarks reverberated around London’s drawing rooms for days following their first appearance and his personal life, as recounted in his columns, was as familiar to the world at large as the latest episode of the Archers. He had seized on a highly successful technique: he sold the man, not the subject matter. You read his columns to find out about him. It had been a fabulous transformation of a man who had missed so many boats by his mid-thirties. He had been a dyslexic schoolboy scarcely able to read or write, and an unsuccessful painter turned alcoholic. He filed his pieces by dictating to a copy-taker. I never saw him drink – he had put all that behind him; his fixes came in the form of strong black coffee and fags. We used to joke that the initials ‘AA’ stood for ‘Alcoholics Anonymous’, but it was possibly no less than Gospel truth.

As restaurant critic for the Sunday Times he emerged onto the same circuit as me. I had a strange brief at the FT. I was separated from my colleagues on the page by ‘Japanese screens’ as my editor put it. I could write about food and foreign restaurants, but no recipes and not London, and all drink excluding wine under 15 percent. I used to see Adrian at launches which were many and plentiful then and usually irrigated by oceans of free booze. It was the period when restaurant PR was largely in the hands of the late Alan Crompton-Batt, who used his bevy of gorgeous, pouting ‘Batt-Girls’ to lure hacks towards openings and convince them to turn in sympathetic write-ups.

Crompton-Batt was not unique: there was – for example – the late Conal Walsh, inevitably dubbed ‘Anal Douche’, who did PR for the Chez Gérard Group among others. Conal used to organise meetings of the Carnivores’ Club, where hacks came in fancy dress (generally smeared with ketchup) to celebrate the consumption of flesh and blood and someone was generally asked to prepare a speech. I remember when it was Adrian’s turn, and watching how nervous he was behind that fierce, but slightly mean exterior that often had me wondering whether he was part Sicilian. He spoke at length, tossing sheets of paper on the floor as he ran down foreign food at the expense of British, lambasting non-saturated fats like olive oil in favour of dripping. My mind went back to the pots of festering fat that used to sit on top of the chimney piece in our childhood kitchen. People said he spoke with authority about food because his brother Nick was a chef. Again it was only after his death that I learned that he took any practical interest in it and that he enjoyed cooking at home.

He was a forthright critic and his astonishing gift for words and phrases meant that much of what he wrote remained memorable. It was the first flush of ‘Modern British Cuisine’, a time when British chefs tended to an exaggerated belief in their own talents – if not sanctity. They were easily offended. When Gill or the other more savage critics dished them they resorted to wrapping up dead animals or other noisome things in parcels and sending them round to the transgressor. Adrian naturally wallowed in their injured pride.

As well as being restaurant critic of the Sunday Times he doubled up as the paper’s television reviewer. I never understood why (beyond the extra earnings) anyone should want to do such a thing. I had always subscribed to the view that an hour spent watching television was an hour wasted. I must have challenged him, saying I’d rather read a book, but he was not having any of it: ‘That’s like saying you can’t have sex and wank!’ I didn’t know then that he actually found it very hard to read a book. Television was that much easier.

With his loud support for native food he had an air of Hogarth’s ‘Britophil’ about him then and I was surprised to learn that he had been such a passionate Remainer at the time of the June Plebiscite. Various friends expressed concern that he was scoring cheap victories when he once wrote a piece decrying German food and his finely chiselled features appeared at the top of the page peering out from under a coal scuttle helmet or a Pickelhaube. I didn’t read the piece but the next time I ran into him I asked him about it. ‘But I copied the whole thing from you!’ He said he had been in Weimar and had seen an article of mine framed on the wall of the Hotel Elephant and used it as the basis for his own piece. I had no idea if he was telling the truth but I had written a story or two about Weimar. Anyway, he efficiently ripped the carpet out from under my feet.

We were never great friends, but he was never nasty to me in the way he turned on so many others. I remember once when one of my children was ill and he spoke with great sincerity about what it was like to be worried about a sick child. He could be very cruel. Obituaries have cited his treatment of Mary Beard and Claire Balding. He seemed to have had an animus against the historian Andrew Roberts whom he called ‘the Pink Prawn’ as a result of his short stature and often florid complexion. Whenever Andrew’s name came up a wicked glint appeared in Adrian’s eye. On one occasion I was at the Bad Sex Awards in the old Astor mansion in St James’s Square and Nancy Sladek (I think it was) asked me to find Adrian as his novel had won the prize. I found him lurking by the door near the stairs and told him I was not to let him out of my sight. At that moment Roberts arrived on the crowded landing. ‘There’s the Pink Prawn wearing a Guards’ tie!’ said Adrian (I think it was a Garrick Club tie, but what the hell), with that he reached into the thicket, grabbed Roberts by the tie knot, hoisted him up to face height, kissed him fully on the lips and tossed him back into the melee. A bemused Roberts scuttled away, his face redder than ever.

For me there were just too many enemies of promise and I dropped out early, while Adrian went from strength to strength, from sleb to über-sleb; a proper, solid talent sustaining him to the last. The last time I saw him was in the chichi Delaunay brasserie in Aldwych two or three years ago. I had been to an execrable performable of Edward II at the National Theatre with some fellow Gavestonians and they were kind enough to treat me to dinner afterwards. I saw him sitting alone at a large table, evidently waiting for his guests. I reminded him who I was and he gave me a faltering smile and a hand to shake but I rather doubt now he even remembered me from Adam.