FURTHER DETAILS ON THE FOLIOS

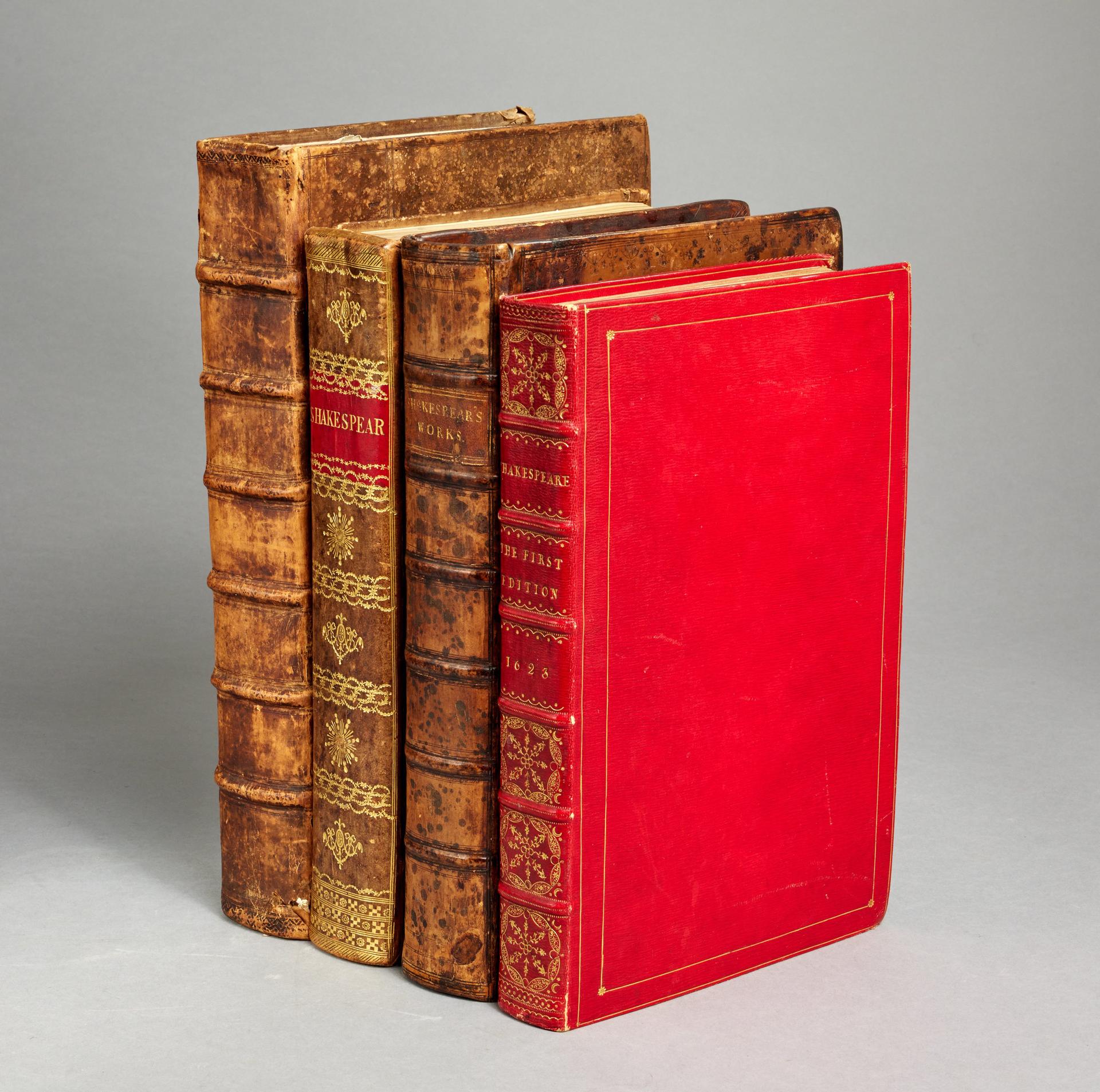

- The first Folio and its successor Folios were published between 1623 and 1685. The initial print-run – opinions vary, but probably around 750 copies – was exhausted within ten years. This led to the publication of the Second Folio in 1632. The two decades that followed were amongst the most tumultuous in British history, and for much of the time the theatres were closed so the plays were not performed, but Shakespeare retained his appeal to readers and in 1664 a new edition appeared with the addition of seven further plays (Pericles and six spurious attributions) to entice readers. A fourth Folio followed in 1685, completing the sequence.

- The four Folios gradually stopped being reading texts and were left as evidence of how Shakespeare’s plays were treasured and preserved in the decades following the author’s death, and thus came to assume their place as a uniquely precious tribute to the greatest writer of the English language.

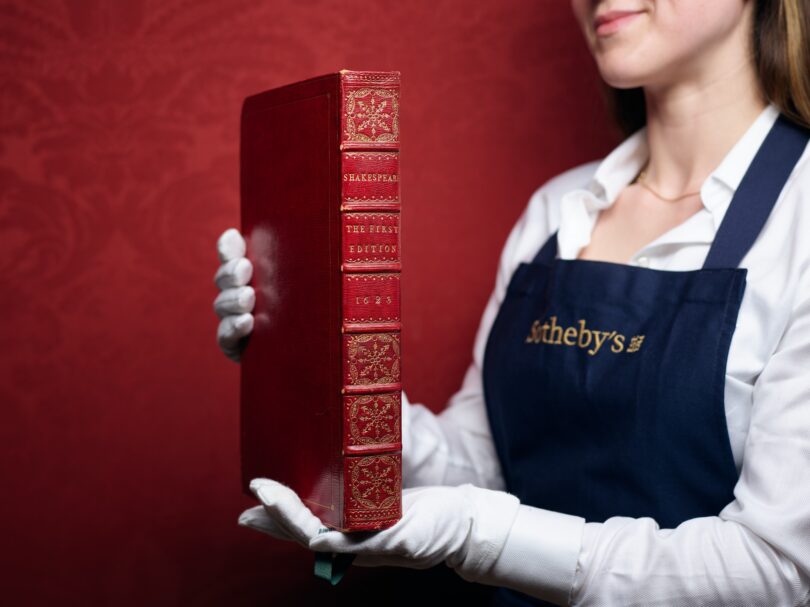

- In the twentieth century it was not unknown for all four folios to be offered as a set – at least six sets were sold by Sotheby’s between the 1930s and the 1980s – but as the number of copies in private hands has dwindled, this has become increasingly rare.

- To his contemporaries and immediate successors, the First Folio and its three successors were above all noteworthy as monuments to their author. The Folios were large, expensive, and prestigious publications that embodied a claim that Shakespeare, a professional writer in the commercial theatre (rather than a poet writing for an elite), had created a legacy that deserved to be passed down the ages.

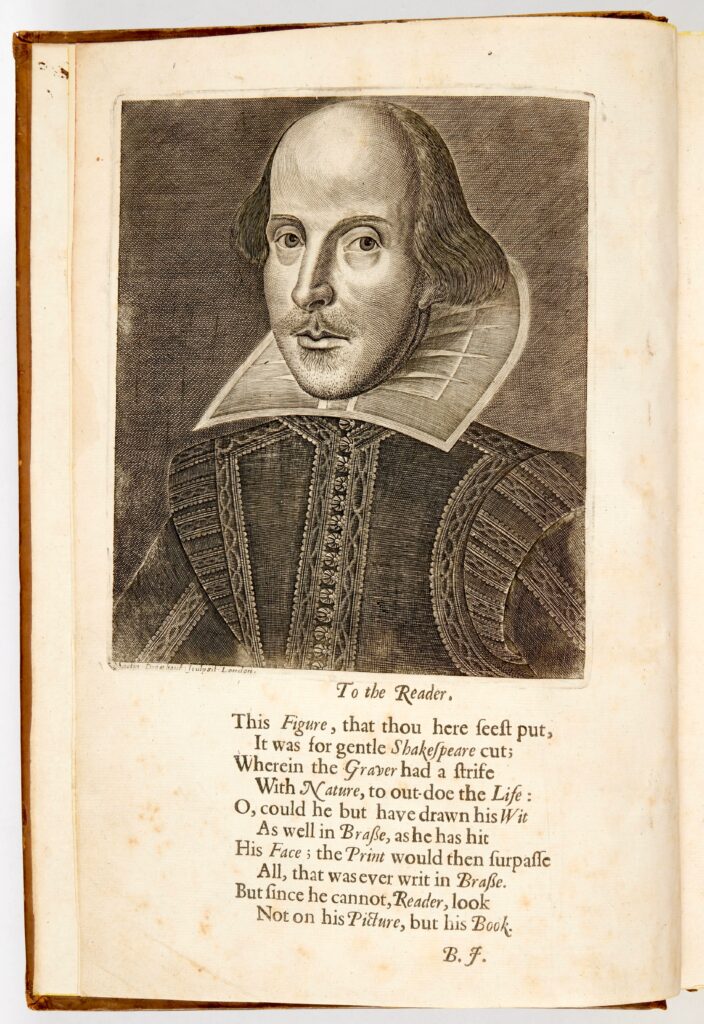

- The two men at the heart of the project that resulted in the First Folio were close friends of Shakespeare. John Heminges and Henry Condell were fellow actors and shareholders in the King’s Men (the acting company to which Shakespeare belonged for most of his career). Shakespeare called them his “fellows” in his will and left them, along with Richard Burbage (d.1619; the leading actor in the King’s Men), money for a mourning ring. Perhaps the dying Shakespeare himself encouraged his friends to collect his plays.

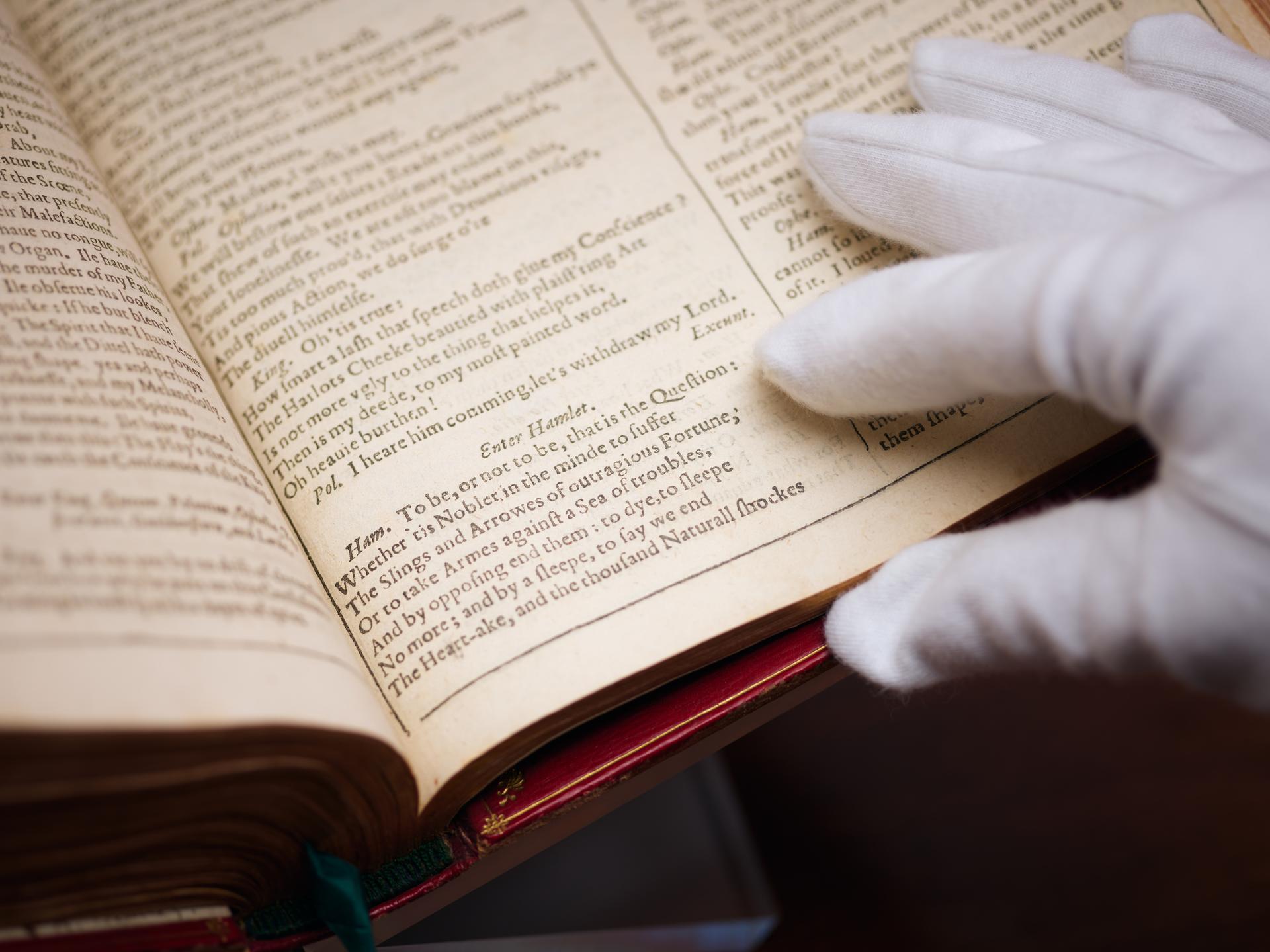

- The First Folio contains thirty-six of Shakespeare’s plays, printing eighteen of them for the first time. Without the Folio, the following eighteen plays may well have been lost for ever: All’s Well that Ends Well, Antony and Cleopatra, As You Like It, The Comedy of Errors, Coriolanus, Cymbeline, Henry VI part one, Henry VIII, Julius Caesar, King John, Macbeth, Measure for Measure, The Taming of the Shrew, The Tempest, Timon of Athens, Twelfth Night, The Two Gentlemen of Verona and The Winter’s Tale.

- The Folio was printed at the shop run by William Jaggard and his son Isaac in London’s Barbican. They ran one of the larger printing houses in London and had the monopoly to print playbills, and so would certainly have been known to Heminges and Condell. Printing the Folio was a large job. Paper will have been the biggest expense: each copy of the Folio required 227 sheets of crown paper, and the total cost of the paper needed for 750 copies will have been nearly £100. Work began early in 1622 but was interrupted several times and only completed towards the end of November 1623. By the beginning of December, the book was published.

- The earliest recorded purchase of the First Folio was on 5 December 1623, when Edward Dering bought two copies (for £2), the first in a long line of purchases of this monumental record to our greatest writer.

- By the early 1630s there was an appetite for a new edition of Shakespeare’s plays. This meant that the First Folio had sold out within a decade, which was a short period for an expensive work of literature by an author who had been dead for nearly twenty years.

- Although only nine years had passed, by 1632 most of the individuals who had been involved in publishing the First Folio were dead. The book was printed by Thomas Cotes, who had taken over the Jaggard printing house in the Barbican as well as their publishing rights. The Second Folio was a page-for-page reprint produced in the same printing house as the First Folio, using the same stock of types and ornaments.

- The text of the Second Folio was taken from the First Folio with some obvious errors corrected, but others inadvertently introduced. It was not recognised at the time that the quality of the text of the Folios tended to decline with each reprint, so it was common for earlier Folios to be discarded when a new edition was published.

- Samuel Pepys bought a Folio in 1664 but he ridded himself of this copy when he bought a new Fourth Folio in 1685, whilst the Bodleian Library famously disposed of their copy of the First Folio as a duplicate in the 1660s. It was only later in the eighteenth century that the textual importance of the First Folio came to be recognised.

- Charles I read and annotated a copy of the Second Folio whilst imprisoned in the later 1640s (this copy is now one of the treasures of the Royal Collection).

- The Restoration of the monarchy in 1660 was soon followed by the reopening of the theatres. The Restoration stage differed significantly from its predecessor – women actors now appeared on stage, and gone were the open-air amphitheatres that brought together a wide cross-section of London society – but Shakespeare was still commonly performed.

- The Third Folio was published in 1663 but the following year it was reissued with a new title-page announcing the inclusion of seven additional plays “never before Printed in Folio.” Only one, Pericles, is now believed to be by Shakespeare. The Third Folio is the rarest of the Four Folios. The Shakespeare Census lists 182 extant copies (not much more than half the number of surviving Second and the Fourth Folios). This is almost certainly because a proportion of the stock was destroyed in the Great Fire of London of 1666.

- The Fourth Folio was printed nearly twenty years later, at the end of the reign of Charles II. This was not a page-for-page reprint. It was printed on significantly larger paper to allow more lines per page, and, unlike the three previous editions, plays did not necessarily start on a new page.

|

About Sotheby’s

Established in 1744, Sotheby’s is the world’s premier destination for art and luxury. Sotheby’s promotes access to and ownership of exceptional art and luxury objects through auctions and buy-now channels including private sales, e-commerce and retail. Our trusted global marketplace is supported by an industry-leading technology platform and a network of specialists spanning 40 countries and 70 categories which include Contemporary Art, Modern and Impressionist Art, Old Masters, Chinese Works of Art, Jewelry, Watches, Wine and Spirits, and Design, as well as collectible cars and real estate. Sotheby’s believes in the transformative power of art and culture and is committed to making our industries more inclusive, sustainable and collaborative.

*Estimates do not include buyer’s premium or overhead premium. Prices achieved include the hammer price plus buyer’s premium and overhead premium and are net of any fees paid to the purchaser where the purchaser provided an irrevocable bid.

Stream live auctions and place bids in real time, discover the value of a work of art, browse sale catalogues, view original content and more at sothebys.com, and by downloading Sotheby’s app for iOS and Android.

# # #

|

|

|